In recent years, consumers have found evidence to suggest that some Chinese manufacturers use prison labor to fulfill demands from multinationals. How these manufacturers contract prisoners and how their use of prison labor becomes hidden in the supply chain are questions that could easily go unanswered by supply chain investigators.

What Does Prison Labor in China Look Like?

China’s “reform through labor” system, also known as “Laogai” (劳改), has existed since the early 1950s. The most recent, high-profile example of this ideology taking root is the Uyghur re-education camps in Xinjiang Province, officially called Vocational Education and Training Centers.

In theory, Chinese forced labor should never touch global supply chains. In 1991, China banned the export of goods produced using reform through labor, and in 2013, government officials announced it would end all reform through labor by the end of that year.

In practice, consumers have discovered that many Chinese manufacturers take advantage of forced labor in prisons and re-education camps. Because there is no clear way of knowing how and where the “reform through labor” law is being implemented, forced labor can still occur undetected within conventional prisons in China.

How Can Analysts Identify Signs of Potential Prison Labor?

It can be difficult for responsible sourcing teams to know which Chinese companies use forced labor. Risk audits often rely on company-provided information and site visits. But there are easier ways to identify high-risk suppliers. Public data provide indicators that a company may use forced labor. These include:

- Addresses

- ID numbers

- Chinese and English names

Querying those indicators shows the scale of the problem. Close to 4,200 Chinese companies have the word “prison” (监狱) in their name and/or address, according to public records from China’s State Administration of Industry and Commerce (SAIC). Thousands more are subsidiaries, parent companies, or other related entities with no other obvious ties to prisons. Still others are owned, directly or indirectly, by Prison Administration Bureaus (监狱管理局)—Chinese government entities that manage prisons within their respective provinces.

Case Study: The Jiangxi Prison Industrial Network

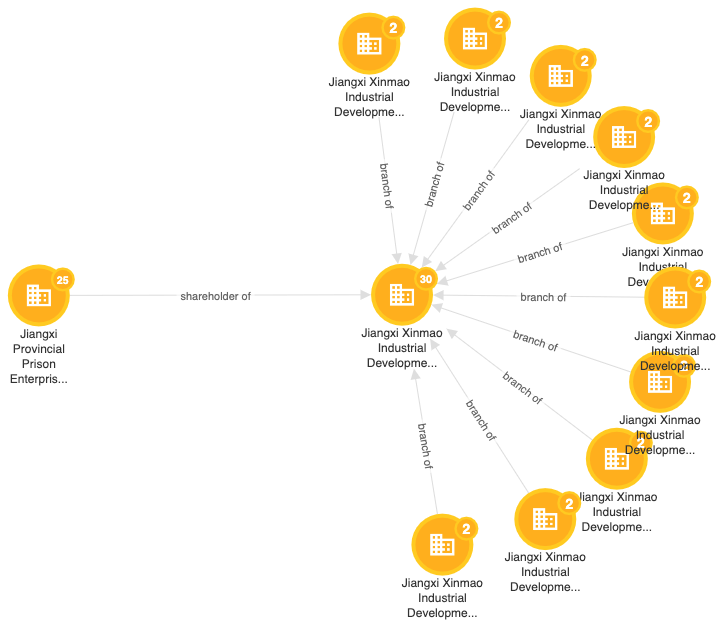

One way prison labor may still occur in China is through the Prison Bureau Administration holding company structure. For example, the Jiangxi Province Prison Bureau (江西省监狱管理局) ultimately controls more than 97 companies through its 100 percent ownership of the Jiangxi Province Prison Group (江西省监狱企业集团公司). Many of these subsidiaries have no obvious ties to the Prison Bureau and all of them pose a high risk of using forced labor.

Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial Development Co. Ltd. (江西新茂实业发展有限公司) is one of the Jiangxi Province Prison Group’s 22 wholly-owned subsidiaries. A public tender announcement dated March 19, 2020 states that Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial Development has begun accepting bids for a prison uniform procurement project. This announcement further bolsters the possibility that Jiangxi Xinmao employs prisoners. However, Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial’s name and address leave no indication that the company is owned by a prison bureau.

Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial’s registered address is “Bajing Town, Gao’an City, Jiangxi Province” (江西省高安市八景镇). It controls 10 factories, seven of which are garment factories that are also registered in Bajing Town.

Fig 1. Snapshot of Jiangxi Province Prison Bureau network in Sayari Graph showing one of its 22 wholly-owned subsidiaries, Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial Development Co. Ltd. The number at the top of each icon is the number of second-tier subsidiaries and/or other shareholding relationships.

Digging Deeper: Chinese Media Coverage on Bajing Town Prison Labor

Bajing Town is home to a Gajing Men’s Prison, where inmates work in in-house factories, according to Chinese language news reports. An article from 2017 posted on Sohu, a Chinese news aggregator, describes the prison’s layout as “similar to an average factory,” with “dormitories, factory areas, infirmaries, and canteens.”

On November 22, 2017, a user posted on Baidu Zhidao, a popular online forum in China, claiming that Ganxi Prison inmates work in garment manufacturing, adding that prisons have “basically transformed into light industries.”

These posts about Ganxi Prison do not explicitly mention Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial Development Co. Ltd. or its affiliated factories. But given their shared location, involvement in garment manufacturing, recent purchase of prison uniforms, and the fact that Jiangxi Xinmao’s sole shareholder is the Jiangxi Province Prison Group, it is possible that Jiangxi Xinmao Industrial and its related companies use Ganxi Prison labor.

The goods manufactured at Ganxi Prison appear to be sold to customers across China, and possibly the world. The 2017 news article posted on Sohu reports that goods manufactured at this prison are shipped to “various locations,” including Guangdong Province, one of China’s largest trade hubs. From here, it is possible that these goods are then exported to other parts of the world.

Using Public Data to Mitigate the Risk of Prison Labor in Supply Chains

While it is ostensibly illegal in China to export goods that are manufactured using prison labor, manufacturers with no surface-level ties to prisons continue to profit off of laborers working in unfree conditions. Given the complexity of supply chains in China, companies purchasing these goods may be unaware that their suppliers are directly connected to Chinese prisons, and thus could potentially be purchasing goods derived from forced prison labor. As the above-mentioned case demonstrates, supply chain investigators can leverage public data to mitigate this risk.