The illicit gold trade continues to challenge global anti-money laundering (AML) efforts, as shown in “the FinCEN Files,” a collection of more than 2,100 leaked Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed by financial institutions with the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

The FinCEN Files and subsequent reporting by multiple outlets, including the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), highlighted the case of Dubai gold trader Kaloti Precious Metals (KPM). KPM remains in operation despite a track record of questionable practices that include over $9 billion in suspicious transactions and a multi-year investigation by a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) task force.

Public records can quickly map KPM’s extended commercial network and gold sourcing patterns. In this analysis, we used public records to confirm both KPM’s ties to a Swiss refinery that journalists have alleged sourced conflict gold from KPM, and KPM companies importing gold from high-risk jurisdictions.

When drawing conclusions from the FinCEN Files, it is important to remember that financial institutions (FIs) file SARs to alert authorities to suspicious transactions with potential links to money laundering and other financial crime. SARs do not confirm criminal activity, and KPM does not face criminal charges and denies any wrongdoing.

Gold trade attractive for money laundering

Money launderers are incentivized to use gold because the gold trade is cash-intensive, and regulations are lax and provide a level of anonymity for traders, according to a 2015 report from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). In addition, gold is easy to transport, relatively stable in price, and it is difficult to maintain provenance.

Money launderers begin by using gold suppliers with lax due diligence processes, a history of dealing in illegal gold, or both. The launderer often will purchase illegal gold in cash and obtain fake receipts to provide a veil of legitimacy, then resell it somewhere else, thus laundering the illicit cash.

When the proceeds come in the form of smuggled or illegal gold, the launderer will undertake what is known as gold laundering — smelting the illegal gold with legal gold before casting it into bullion. There have been reports of illegal gold bars finding their way to vaults in major FIs as recently as 2019.

KPM subject of DEA investigation citing “primary money laundering concern”

ICIJ reporting on the FinCEN Files revealed a three-year investigation by a DEA task force into KPM’s operations. The DEA investigation reportedly found AML red flags, including cash payments worth millions of dollars to KPM’s suppliers and cash withdrawals from KPM’s Dubai bank account so large they had to be carried out in wheelbarrows. The task force suggested identifying KPM as a “primary money laundering concern” under Section 311 of the PATRIOT Act. However, the U.S. Treasury did not follow through for fear of upsetting the United Arab Emirates (UAE), according to investigators who worked on the case.

A separate investigation from the BBC alleged that KPM was part of a major international drug money laundering operation. French authorities convicted 27 members of an international money laundering gang in 2017, after they used drug money to purchase 3.6 tonnes of black market gold in Europe and resell it to KPM. Neither KPM nor its founder, Munir Ragheb Al-Kaloti, were charged with a crime.

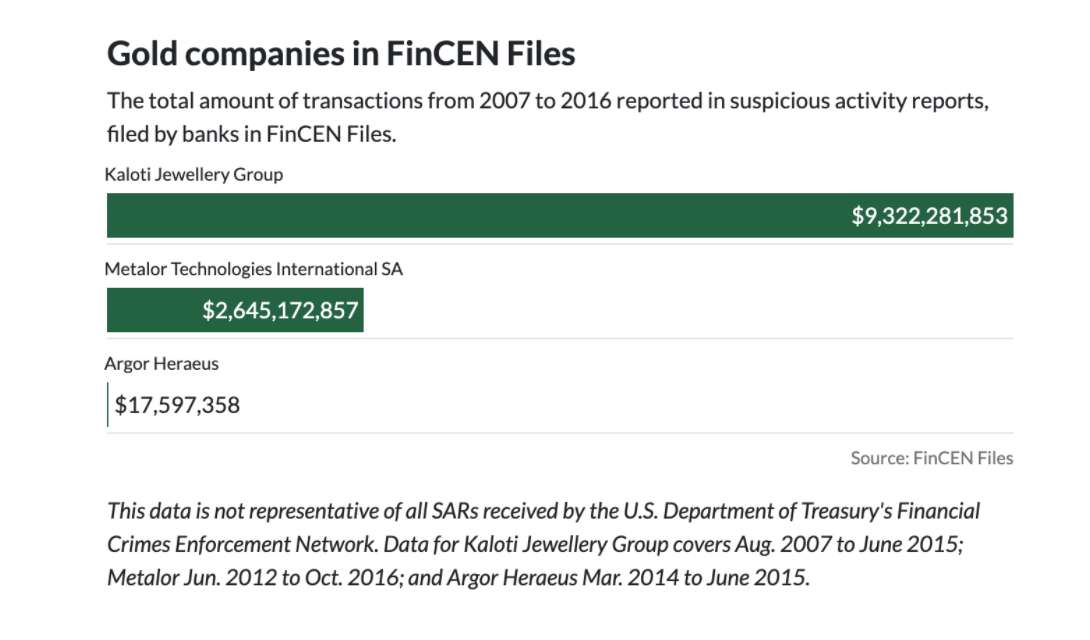

The SARs included in the FinCEN Files underscore KPM’s questionable history. The FinCEN Files account for only 0.02 percent of the SARs filed in the time period covered, which means there could be more SARs linked to other precious metal suppliers that we cannot analyze. Even so, in the files available a disproportionate volume of suspicious transactions are linked to the Kaloti network, compared to transactions linked to other precious metals suppliers.

Fig. 1: An illustration from ICIJ that compares the SARs linked to KPM — listed here as Kaloti Jewelry Group — with those linked to other major precious metal companies.

Records confirm refinery ties, high-risk sourcing from Colombia

Supplier relationship reveals potential risk

First, UAE corporate data sheds light on the companies KPM supplies with gold. A 2020 Global Witness report alleged that KPM has a history of purchasing gold from mines controlled by Sudanese paramilitary groups involved in human rights abuses and re-exporting to Valcambi. UAE corporate data partially corroborates the Global Witness account by indicating that KPM has or has had a supplier relationship with Valcambi.

This relationship could expose FIs to potential risk in their gold supply chain, if the allegations regarding KPM sourcing conflict gold are true. Valcambi is listed on the London Bullion Market Association’s (LMBA) Good Delivery List. The LMBA maintains stringent standards for which entities they accredit and place on the list, which is “used by many markets and exchanges for defining, in whole or in part, the deliverable brands within their jurisdictions,” according to the LMBA website.

U.S.-based Kaloti Metal and Logistics importing high-risk Colombian gold

Second, public records confirm that KPM has a history of importing gold from high-risk jurisdictions. Trade data from Panjiva shows that Florida-based Kaloti Metal and Logistics (KML), KPM’s U.S.-based company, imported roughly $72 million worth of gold from Colombia between October 2015 and April 2018.

Colombian gold is inherently risky because of illegal gold smuggling and illegal domestic mining. Colombia exported 64 tons of gold in 2016, even though its major, legal mining operations produced only eight tons in that same year.

Experts attribute this disparity in part to narco traffickers purchasing illegal gold from neighboring countries, such as Panama, Venezuela, México, and Chile, and then smuggling it into Colombia before selling it to local traders. Another major factor is illegal extraction operations controlled by criminal syndicates or paramilitary groups, including the FARC and the ELN. The illegally sourced gold, whether from mining or smuggling, is laundered within Colombia before being exported to major gold traders globally.