Between November 2017 and December 2019, Ukrainian aircraft engine manufacturer Motor Sich JSC sent more than $250 million worth of helicopter engine parts destined for Russia through Bosnia and Herzegovina, according to trade data.

The three companies used in the scheme are ultimately controlled by Motor Sich, several individuals connected to the Russian military, and a Bosnian-Serb with previously unreported crossover with several pro-Russian elements related to the war in Eastern Ukraine.

The arrangement was first uncovered by Ukrainian media in July 2019, but has continued unabated since then.

While we were unable to confirm the precise final use case of the engine parts, the trade arrangement raises serious questions about Ukrainian companies’ ongoing support of Russia’s defense industry given the active war between the two countries. It also demonstrates the importance of neutral states—in this case, Bosnia and Herzegovina—in facilitating problematic trades between warring nations.

“We have solved the problem with aircraft engines”

Amid continuing tensions over the conflict in Ukraine, the Russian government has made repeated public statements about successfully shifting its defense sector away from Ukrainian imports—particularly from Ukrainian aircraft engine parts.

Vice Premier of the Russian Federation Yuriy Borisov declared in May 2018 the country’s independence from Ukrainian engine parts, according to local media. “I can state that there is no longer a dependence on Ukrainian production,” said Borisov. “We have solved the problem with aircraft engines, the VK-2500 has replaced the TV3-117 in military aviation.”

Historically, Russia has relied on Ukraine for aircraft engines for both military and civilian use. The TV3-117, produced by the Ukrainian joint-stock company Motor Sich, has long been a fixture in a multitude of Russian military helicopters, including the Mi-24 gunship and Mi-28 attack helicopter.

This reliance is in part due to the historic cross-border collaboration between two firms: the aforementioned Ukrainian Motor Sich and the Russian UEC-Klimov JSC.

In 2014, then-President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko issued an order banning exports of military equipment to Russia. While the measure curbed a significant amount of Ukrainian defense exports to Russia, it has failed to completely stop it, as the two countries’ historical trade has been disproportionately dependent on military goods.

Since that legislation and amid an increasingly sour relationship, the Russian defense sector likewise is keen on replacing much of its imports through domestic production.

Ukrainian parts from Bosnia and Herzegovina

On Nov. 29, 2017, six months prior to Borisov’s declaration of independence from Ukrainian parts, Motor Sich in Ukraine sent several shipments of parts labeled “Spare parts for engines TV3-117VM series 02, TV3-117VMA series 02, for civilian aviation” to Bosnia and Herzegovina’s northeastern city of Bijeljina, according to commercial trade data. The data lists the recipient of this shipment as Inžinjering – BN Bijeljina D.o.o., a company registered in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Bosnian-Serb entity.

The shipment is broken down into 20 individual shipments with a total weight of approximately 121.4 kilograms and a combined value of UAH 8,264,850 (~$315,000), according to Ukrainian trade data. Just under two months later, on Jan. 22, 2018, a set of 19 shipments with the same combined weight was exported to Russia by Inžinjering – BN Bijeljina D.o.o.

In Russia, the consignees importing these shipments were two Russian companies: Vertoletnye Kompleksy i Mnogofunktsionalnye Sistemy LLC (VKMS LLC) and Dvigateli “Vladimir Klimov-Motor Sich” CJSC (VK-MS CJSC).

We confirmed multiple sets of shipments following this pattern between November 2017 and December 2019.

| Ukraine Export Data (to Bosnia and Herzegovina) | ||

| Departure Date | Number of Shipments | Combined Weight (kg) |

| 2017-11-29 | 20 | 121.73 |

| 2018-02-05 | 39 | 152.45 |

| 2018-02-15 | 25 | 428.82 |

| 2018-02-27 | 35 | 181.59 |

| 2018-03-19 | 49 | 97.95 |

| 2018-04-11 | 31 | 117.68 |

| 2018-04-27 | 44 | 493.43 |

| 2018-06-19 | 43 | 167.71 |

| 2018-08-29 | 32 | 280.79 |

| 2018-09-25 | 19 | 70.34 |

| 2018-10-09 | 38 | 146.77 |

| Russia Import Data (from Bosnia and Herzegovina) | ||

| Arrival Date | Number of Shipments | Combined Weight (kg) |

| 2018-01-22 | 19 | 121.74 |

| 2018-02-11 | 35 | 152.45 |

| 2018-02-23 | 24 | 428.82 |

| 2018-03-11 | 35 | 181.60 |

| 2018-03-28 | 31 | 97.98 |

| 2018-04-20 | 30 | 115.84 |

| 2018-05-10 | 44 | 493.44 |

| 2018-06-27 | 42 | 167.71 |

| 2018-09-07 | 32 | 280.79 |

| 2018-10-01 | 18 | 70.34 |

| 2018-10-15 | 37 | 146.78 |

Fig. 1: A sample of trade data showing the sets of shipments from Ukraine to Russia via Bosnia and Herzegovina. Note the corresponding weights and numbers of shipments.

This trading pattern—shipments of engine parts arriving in BiH and departing for Russia a few days later—continues through October 2019, at which point Russian import data ends. Ukrainian export data indicates that parts shipments to the Bosnian company continued through December 2019.

Interestingly, the import data reported by Russia only specifies the parts themselves, and not the ultimate use case. For example, the data lists things like “parts for turbojet and turboprop engines” and “gaskets.” However, the Ukrainian export data is more telling. In addition to listing the specific part, the entries in the Ukrainian data also reveal which engine the part is for. On Jan. 22, 2018, Russian import data lists a 54.18 kilogram shipment of “miscellaneous shafts” from the Bosnian company. On Nov. 29, 2017, Ukraine export data lists a shipment with an identical weight as:

1. Spare parts for engines TV3-117VM series 02, TV3-117VMA series 02, for civilian aviation: Shaft transmission: 0780299480-03 Shaft flexible external – 100pcs. 0780260399 Oil pump actuator – 3 pcs. 0780299270-07 Tickle- 5 pc. 0780299290-02 Flexible external shaft – 10 pc. 0780299480-03 Flexible shaft outside – 1 pc. 0780620369-01 Curtain – 8 pc. 0780141112 Axle – 10 pcs. 0780260399 Oil pressure actuator – 3 pcs. 0780620369-01 Valik – 7 pieces 0780850127 Ressoor – 30 pcs.

Concurrent defense contracts

From the Ukrainian export data it is clear that VKMS LLC was importing parts for the civil variant of the TV3-117 helicopter engine. VK-MS CJSC, on the other hand, was importing parts for the civil variant of the AI-9V starter engine – an auxiliary unit used to start the TV3-117.

While the trade data seems to show strictly non-military purposes, examination of VK-MS CJSC’s procurement history indicates this may not be the case.

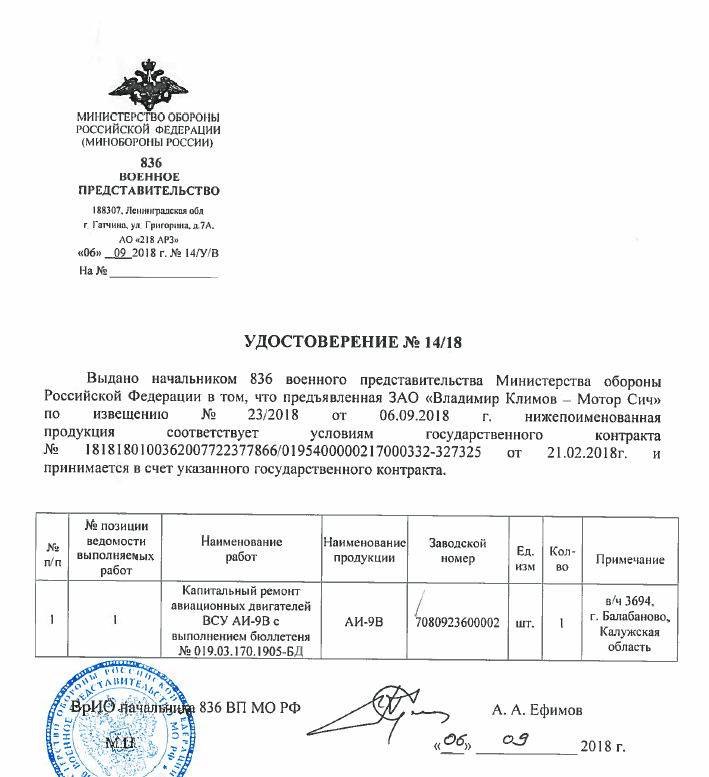

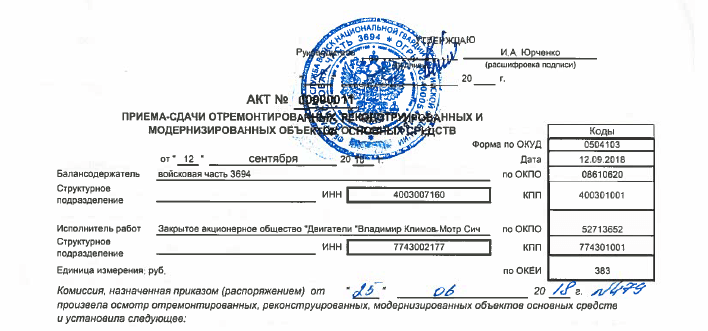

A search for VK-MS CJSC in an official Russian procurement database reveals that the company had one open contract in 2018 that concluded in December. In the contract, signed in February 2018, VK-MS CJSC was hired by the Russian National Guard to overhaul 10 AI-9V engines—work on these engines was completed eight months later.

Because 10 individual units were involved, the invoices sent after the completion of the work are broken into 10 parts. Each invoice features a page from the 836th Military Representation (836 Военное Представительство), the Russian Ministry of Defense’s quality control body for military equipment.

Fig. 2: Invoice for the overhaul of one AI-9V engine.

Additionally, each engine’s invoice features a field labeled “asset holder,” indicating who the actual engine belongs to. For every engine, “Military Unit 3694” is listed as the asset holder.

Fig. 3: The form lists the asset holder (балансодержатель) as Military Unit 3694 (войсковая часть 3694).

Military Unit 3694 is a national guard unit under the authority of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. It is based in the town of Balabanovo, just outside of Moscow.

Friends in high places

A closer look at the companies involved in importing helicopter engine parts from Ukraine via Bosnia and Herzegovina reveals direct ties to Russia’s military industrial complex—more specifically—the air transportation arm of the Russian military.

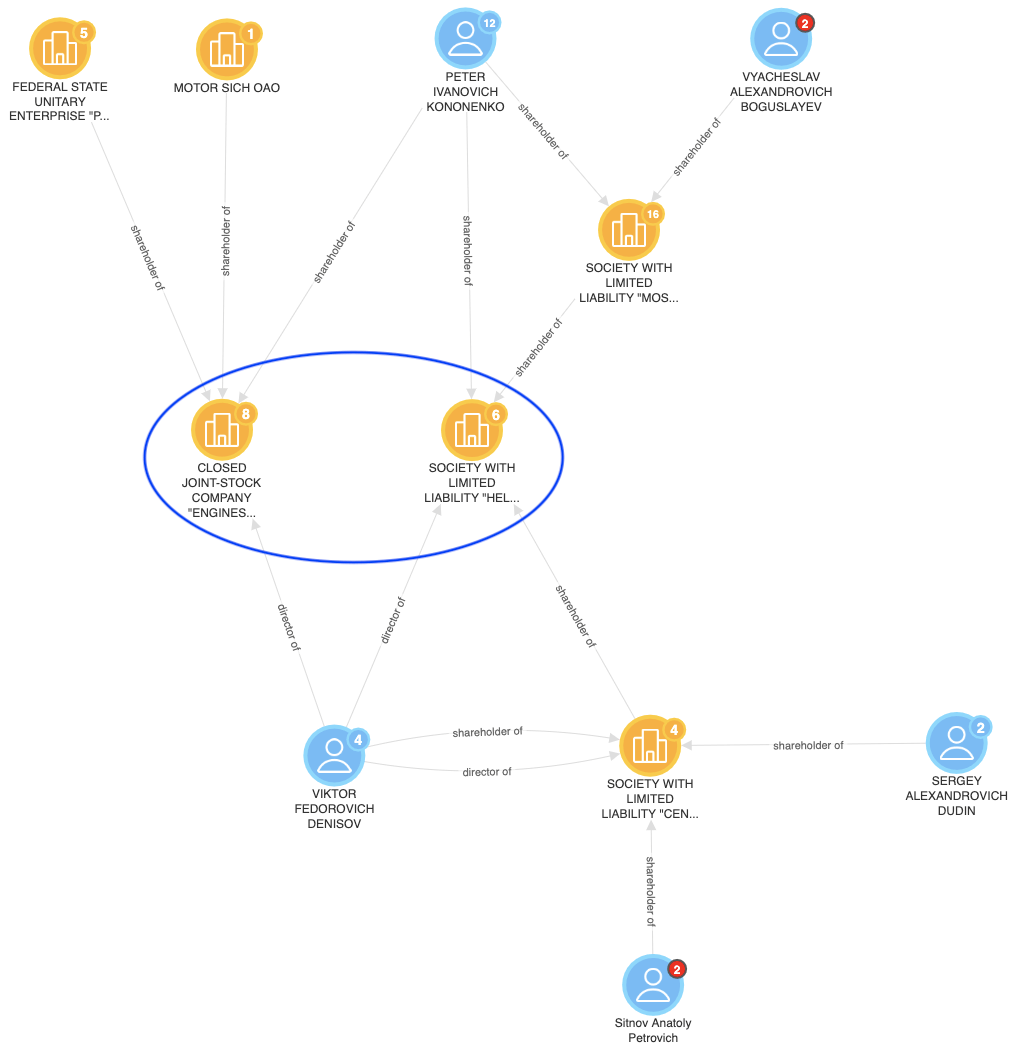

The two Russian importers, VKMS LLC and VK-MS CJSC, are clearly related. In addition to having Moscow addresses down the street from each other, they share the same general director, Viktor Fedorovich Denisov. Denisov is the former commander of the Russian military’s air transportation arm.

VK-MS CJSC was registered in 2002. Its original founders were the state-owned Russian Aircraft Corporation “MIG” (50 percent), Motor Sich (20 percent), and Pyotr Ivanovich Kononenko (30 percent), a Motor Sich director. It is unclear whether the original founders still own shares of the company.

VKMS LLC was founded in 2011, by Losinyi Ostrov LLC (60 percent); Tsentr Issledovaniy, Analiza i Marketinga LLC (20 percent); and Kononenko (20 percent). Losinyi Ostrov LLC is owned by Vyacheslav Aleksandrovich Boguslayev (80 percent), the president of Motor Sich and former Ukrainian MP, and Kononenko. Boguslayev is currently the ultimate beneficial owner of VKMS LLC through his controlling stake in Losinyi Ostrov LLC.

Tsentr Issledovaniy, Analiza i Marketinga LLC is owned by Denisov along with Sergey Alexandrovich Dudin and Anatoly Petrovich Sitnov—each owning approximately a third of the business. Dudin is the finance director of VK-MS CJSC and Sitnov is the president of the board.

Fig. 4: The VKMS LLC—VK-MS CJSC network as it appears in Sayari Graph. VKMS LLC (right) and VK-MS CJSC (left) are circled in blue.

A personal favor for Boguslayev

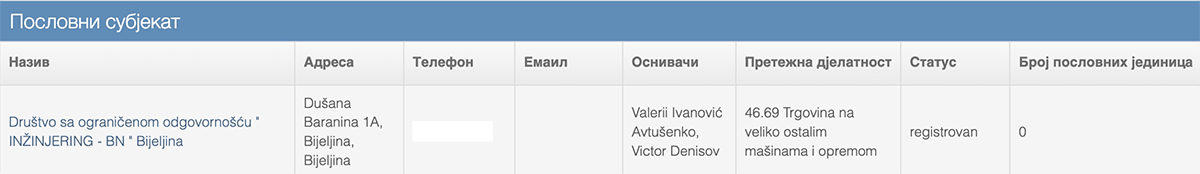

The Bosnian intermediary company, Inžinjering – BN Bijeljina D.o.o., has a slightly murkier background. While the exact date of registration is not listed in the Republika Srpska business register, Google results for the company only begin to appear in 2018.

The founders of the company are Denisov—the general director of VKMS LLC and VK-MS CJSC—and Valery Avtushenko, former deputy head of military air transport as part of the Russian armed forces and the commercial director of VK-MS CJSC.

Fig. 5: Excerpt from the Republika Srpska Register of Business Entities reporting Denisov and Avtushenko as the founders of Inžinjering – BN Bijeljina D.o.o.

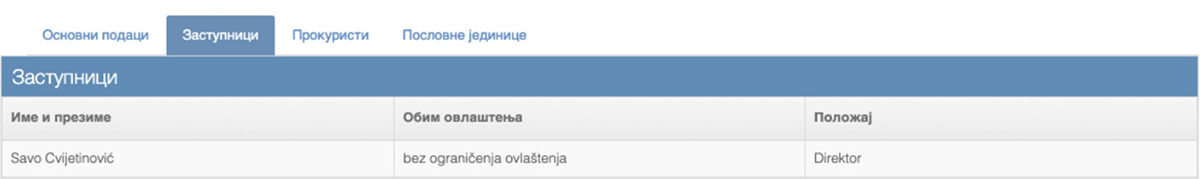

The director of the company, Savo Cvijetinović, is a Bosnian-Serb from Lopare, a town just outside Bijeljina. Cvijetinović is a board member of the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), Bosnia and Herzegovina’s primary Bosnian-Serb party that advocates for secession and closer ties to Russia. He also heads a cultural exchange group called “Serb-Russian Friendship” and in 2016, hosted a delegation of Russian artists in Bijeljina.

Fig. 6: Excerpt from the Republika Srpska Register of Business Entities reporting Cvijetinović as the director of Inžinjering – BN Bijeljina D.o.o.

Cvijetinović claims that he was asked personally by Boguslayev to set up the operation in Bijeljina, according to a call with Ukrainian media.

Serb-Russian Friendship

Throughout Cvijetinović’s history of maintaining the Russia-Serbia cultural relationship, he has crossed paths with several notable individuals given Ukraine’s ongoing conflict with Russia.

At a 2014 conference in Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia commemorating the August anniversary of Russia’s 2008 war in South Ossetia, Cvijetinović was part of a delegation including Serbian pro-Russian political analyst Dragana Trifković, then-Serbian journalist and current Serbian Ambassador to Russia Miroslav Lazanski, and—most notably—alleged PMC Wagner member Oleg Simunyak.

PMC Wagner is a Russian private military company that is active in numerous conflicts around the world and is believed to be operating at the behest of the Russian government. The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned PMC Wagner in June 2017 for sending forces to fight alongside pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine.

The members of the delegation have all been outspoken in their support of the Russian cause in eastern Ukraine, with Simunyak allegedly aiding the Russian forces directly as a PMC Wagner contractor, according to the Security Service of Ukraine.

Simunyak denied working for PMC Wagner in an interview with the Federal News Agency, a Russian news portal alleged to be a sister organization of oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin’s infamous “troll factory,” the Internet Research Agency. Prigozhin is widely believed to be financing PMC Wagner and was sanctioned by OFAC in December 2016.

Simunyak’s ties with the former Yugoslav republics go back to the Bosnian War in which he fought as a Russian volunteer on the Bosnian-Serb side. He has since written extensively about his experiences during the Yugoslav wars under the literary pseudonym Oleg Valetsky.

We were unable to find any mention of Cvijetinović in media coverage of the conference, however he can be seen seated beside Trifković and Lazanski in a photo from the event published by Serbian media.

Fig. 7: Photo published by Serbian media showing Cvijetinović (circled in blue) seated beside Lazanski and Trifković. (Photo: Ceopom Istina)

Additionally, we confirmed his travel to and from the conference along with the rest of the delegation. On Aug. 7, 2014, Cvijetinović and Simunyak flew from Moscow to Vladikavkaz, according to flight data. Following the conclusion of the conference, Cvijetinović, Simunyak, Lazanski and Trifković flew together back to Moscow, on Aug. 9. Finally, on Aug. 10, Cvijetinović and Lazanski both left for Belgrade, Serbia on the same flight.

Conclusion

The ongoing flow of engine parts through Bosnia and Herzegovina highlights several serious flaws in Ukraine’s ability to control its own trade during wartime. Regardless of the final destination of these materials, the fact remains that a Ukrainian entity is actively supplying the ministry of defense of a country with which it is engaged in war. To make matters worse, Motor Sich head Boguslayev—a Ukrainian PM from 2012 until just last year—actively colluded with parties both directly and indirectly involved in the Russian war effort in Ukraine to make it happen.

The most recent trade data that we have access to ends in December 2019, however it seems unlikely that Motor Sich will cease supplying the Russian Ministry of Defense through Bosnia and Herzegovina anytime soon.

Photo: Yevgeny Volkov (CC BY 3.0)