July 30 is the World Day against Trafficking in Persons, proclaimed by the United Nations (U.N.). Trafficking in persons is a serious crime and a grave violation of human rights. Every year, thousands of men, women, and children fall into the hands of traffickers, in their own countries and abroad. Almost every country in the world is affected by trafficking, whether as a country of origin, transit, or destination for victims.

The campaign for World Day Against Trafficking in Persons 2023 aims to raise awareness of the issue and calls on governments to assess and enhance their efforts to strengthen prevention, identify and support victims, and end impunity for offenders.

The U.N. defines Trafficking in Persons as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.” Exploitation can include a number of crimes, ranging from forced labor, slavery, and prostitution, among others.

Importers can support these efforts to raise awareness and promote prevention by operating as enablers of progress. Identifying risks of forced labor and cutting ties with the businesses suspected to use forced labor can financially impact the systems facilitating this crime.

How Enterprises can Identify Forced Labor

With the power of public data, enterprises can do their part to identify forced labor risk within their supply chains. Forced labor risk can come in many forms and the more information businesses have on their suppliers the better they can assess the potential for risk.

Here are a number of ways enterprises can uncover the potential use of forced labor in their supply chains using public data in Sayari Graph:

- Identify Surface Level Forced Labor Risk

To start off, enterprises can weed out the more obvious forms of forced labor risk. While forced labor occurs in many parts of the world, a years-long investigation by the United States into alleged human rights abuses perpetrated on Uyghur, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Muslim ethnic minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) culminated in the enactment of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).

The UFLPA, which went into effect on June 21, 2022, creates a rebuttable presumption that any product “made wholly or in part” in China’s Xinjiang Region is made with forced labor and therefore subject to be detained or seized by CBP.

The starting point for every importer looking to stay in compliance with the UFLPA and removing forced labor from their supply chain should be ruling out suppliers with obvious ties to Xinjiang. This includes situations in which a supplier:

- Matches to entities on the UFLPA entity list

- Contains forced labor keywords in their company name

- Has an address in Xinjiang

- Was mentioned in adverse media regarding forced labor and modern slavery

Sayari Graph flags entities that fall under those categories automatically as high risk – and it can do so at scale. But in the case where an investigator is manually screening entities, there are a few tips to remember. While company names in China are highly structured and will often include the name of the region they are located in, this isn’t always the case. Just because a company doesn’t have “Xinjiang” in its title doesn’t mean it’s are free of ties to Xinjiang and it’s important to always verify its address.

- Uncover Forced Labor Risk in Company Relationships

To go a step further to ensure no ties with forced labor, investigators can go beyond the surface level risk factors and look for risk that is inherent in company relationships. It’s important to look not only at the supplier-centric details, but to also look at its broader corporate network. Sayari Graph can help answer supplier-centric questions, such as: Who owns and controls my supplier? What else do they own and control, and with whom do they do business, directly and indirectly?

This is particularly important when conducting forced labor risk assessments on large companies that own or control multiple key components in a supply chain – also known as vertical integration. The Chinese government actually indirectly incentivizes vertical integration through its mutual pairing assistance program; the program facilitates Chinese companies establishing satellite factories in Xinjiang. This process can hide forced labor risk across several layers removed from the ultimate exporting company in a vertically integrated supply chain.

- Review Forced Labor Risk in Trade Relationships

Not only does Sayari surface forced labor risk in corporate relationships, but it also identifies where risk may enter at the direct or sub-tier supplier level as a result of trade relationships. By overlaying corporate data with trade data, users of Sayari Graph can unearth supply chain risks that are often buried in complex supply chains.

In the UFLPA guidance, CBP has made abundantly clear the need for U.S. importers to have visibility into their entire supply chain all the way back to the raw material inputs. Suppliers outside of China that source raw materials from Xinjiang present enormous obstacles for trade compliance practitioners.

It can be a challenge to discover whether products sourced from another country with lesser known forced labor risk in fact contains raw materials from Xinjiang. For example, since the UFLPA went into effect in June of 2022, CBP has detained over 2,156 shipments of electronics representing $1.3 billion dollars in value; about 99% of those shipments were from countries outside of China (Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand). While about a third of those shipments were eventually released, the detainments suggest the need for importers to better understand who their suppliers are sourcing from – and fast. This is an enormous task, but there are ways to begin to identify transshipment risk with access to the right data and technology.

With layered corporate and trade data in Sayari Graph, trade compliance officers can vet the trade relationships of their international suppliers. While a trade relationship between an entity in Xinjiang and a direct supplier isn’t necessarily an immediate cause for concern, with further investigation a user can see what products were shipped to determine whether that poses a risk for their specific imports.

Supply Chain Risk Assessment in Action

Let’s say you were sourcing polyester strappings from an Indian firm called PLASTIBLENDS INDIA LIMITED. PLASTIBLENDS is India’s largest manufacturer and exporter of additive compounds for the plastic processing industry. To uncover whether there is forced labor risk, you’ll need to dive into who is supplying PLASTIBLENDS with inputs used to manufacture polyester strappings, and whether any of those second tier suppliers present any forced labor risk. Corporate records will not be enough to effectively do this type of analysis, we need to layer that information with trade data.

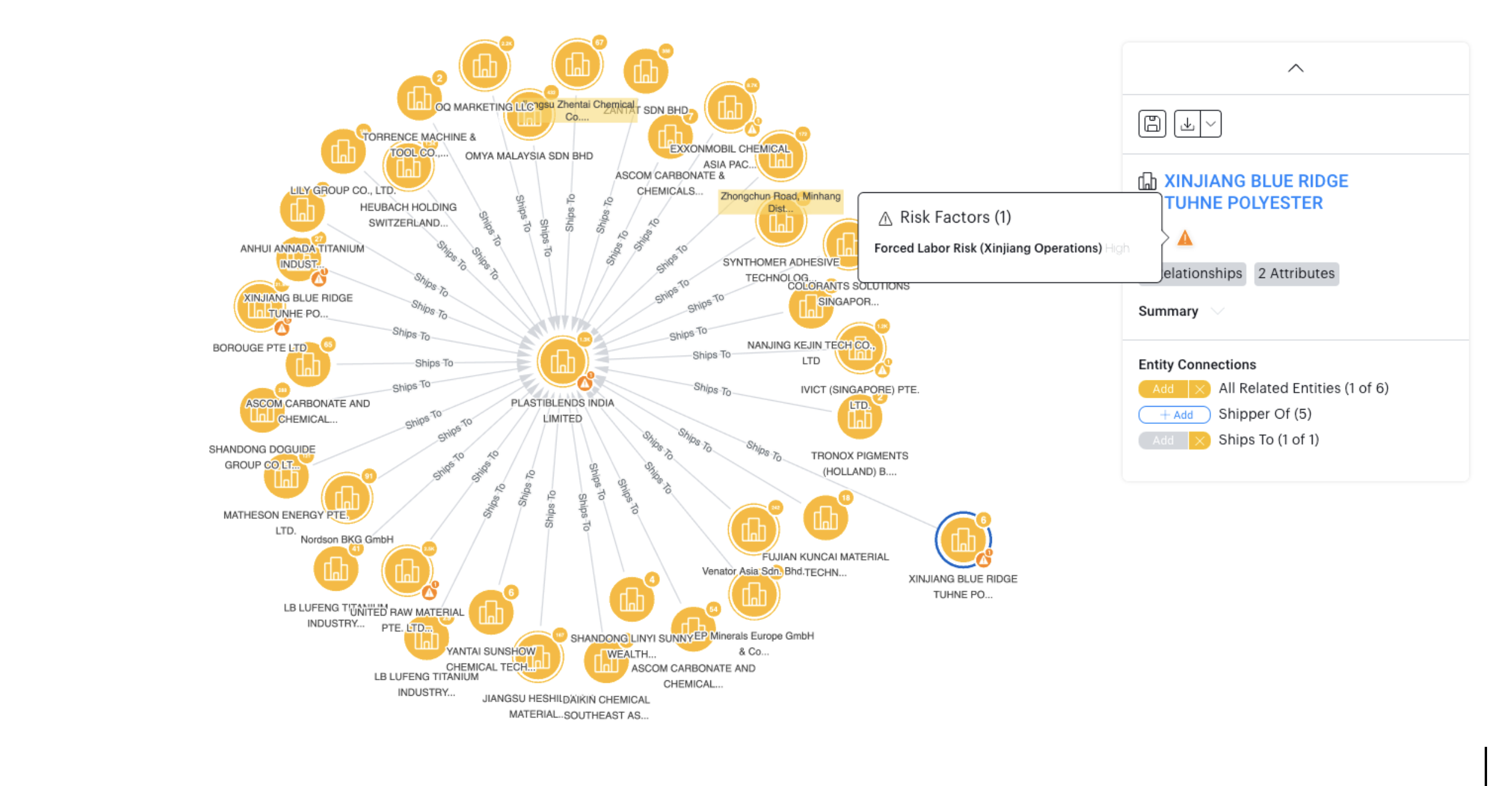

Fig. 1: Sayari Graph network chart of entities that supply goods to PLASTIBLENDS, which includes XINJIANG BLUE RIDGE TUHNE POLYESTER, an entity flagged for forced labor risk.

When we open up the supplier network for PLASTIBLENDS, we see that it has received shipments from a number of China-based entities, in particular XINJIANG BLUE RIDGE TUHNE POLYESTER, an entity flagged for forced labor risk due to its operations in Xinjiang. This identifies a high-risk entity exporting goods to our first tier supplier, PLASTIBLENDS.

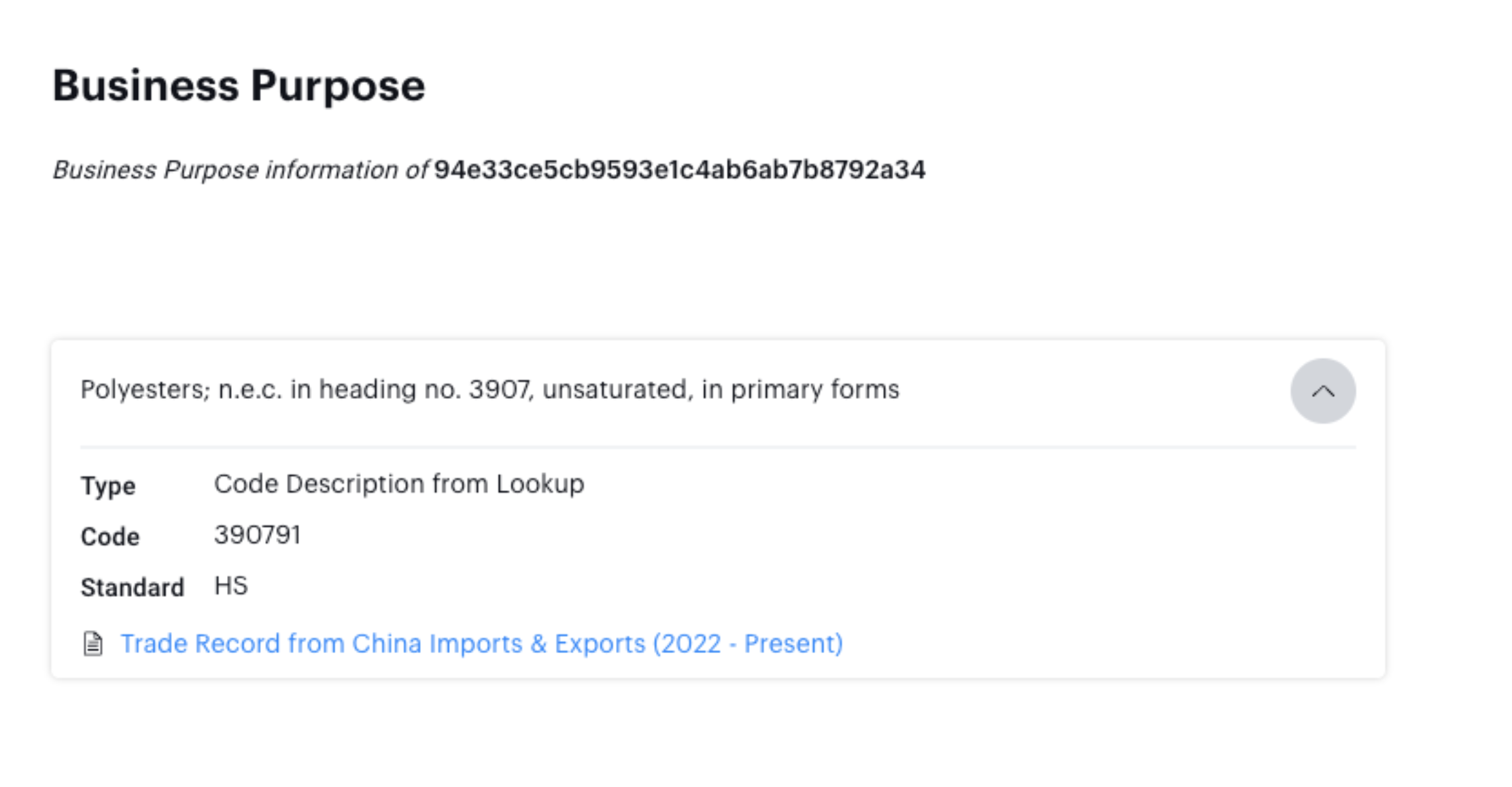

However, a trade relationship between an entity in Xinjiang and a direct supplier isn’t necessarily a cause for concern. We also need to know what PLASTIBLENDS is receiving from XINJIANG BLUE RIDGE. If we’re procuring polyester strappings in this scenario, we’d want to check if XINJIANG BLUE RIDGE is exporting things like polysilicon or cotton to PLASTIBLENDS. When we examine the details of the shipment, we’d see that PLASTIBLENDS imported a shipment of what appears to be polyester raw material from XINJIANG BLUE RIDGE.

Fig. 2: In a Chinese trade record, we can identify the types of products that were shipped to PLASTIBLENDS.

While every company has to determine their own appetite for risk, in this scenario, in this case, PLASTIBLENDS is now at least aware that some of its polyester may be coming from a company based in Xinjiang, a region known for its use of forced labor. This extra step of reviewing a supplier’s trade history can protect an enterprise from hidden forced labor risk and help make strides towards eradicating forced labor.

To watch one of our analysts complete an example investigation, watch our latest webinar Enhancing Xinjiang Forced Labor Risk Assessments.