Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Whether you’re attempting to map out a global money laundering network or to verify the existence of a supplier in foreign jurisdictions, you’re bound to encounter some unfamiliar languages in the course of a cross-lingual investigation.

Even those lucky enough to work on teams with language-enabled analysts or access to professional translation tools and services will eventually need to tackle an investigation in an unsupported language.

Fortunately, you don’t need to be fluent in a language to navigate its texts with more confidence. Conducting investigations in languages you don’t speak is a skill, and this report provides a foundation from which analysts and investigators may begin to cultivate it.

After establishing why proficiency in navigating unfamiliar languages is such a valuable ability, this report explores the many ways words (and in this case, “words” refers mainly to individual and company names) change between languages. Then, building on that knowledge, it provides a method for “reading” public records in unfamiliar languages, closing with two investigative examples that put these lessons into practice.

Competency in Navigating Unfamiliar Languages

Learning how to conduct investigations in languages you don’t speak will make you a much more effective investigator. Not only will it reduce your odds of misinterpreting text in another language, but it will also help you uncover risks you might have overlooked otherwise.

Imagine you work for a financial institution, and a high net worth customer with Russian citizenship and an address in London has been flagged for review. You’re responsible for identifying any potential risk they pose to your institution. With a competency in navigating unfamiliar languages, you’ll be able to find more of those European shell companies and answer critical questions more effectively.

Another reason this competency is an important part of your investigative toolkit is because, from a professional development perspective, demonstrating cross-lingual ability makes you instantly more valuable. As illicit networks become more interconnected across the globe, a range of missions increasingly require analysts and investigators to be adept at conducting investigations outside their primary regions and languages of expertise.

This is not to say that language learning is irrelevant, of course. True language proficiency allows you to move even more quickly and effectively through these investigations, and there will always be certain types of analyses that absolutely require language proficiency.

Still, you can get really far without even elementary knowledge of a specific language – much farther than people commonly think. Effective investigations using public records usually do not require you to read long blocks of text; and even when they do, a loose translation from something like Google Translate can support a lot.

To use these tools effectively, however, you need a very accurate and specific understanding of how target names change between languages.

How Words Change Between Languages

Understanding some of the most common ways that words and names change across languages will allow you to anticipate the many types of aliases you encounter in your research and, critically, avoid false positives and negatives. Looking under the wrong spelling or variant can stop an investigation in its tracks and have costly consequences.

To anticipate the many ways a target may show up in public records, we will spend some time reviewing the differences between translation, transliteration, phonetic transcription, trade names, and naming conventions. The dividing lines between these concepts aren’t always well defined, but the overlap doesn’t complicate their application.

Translation

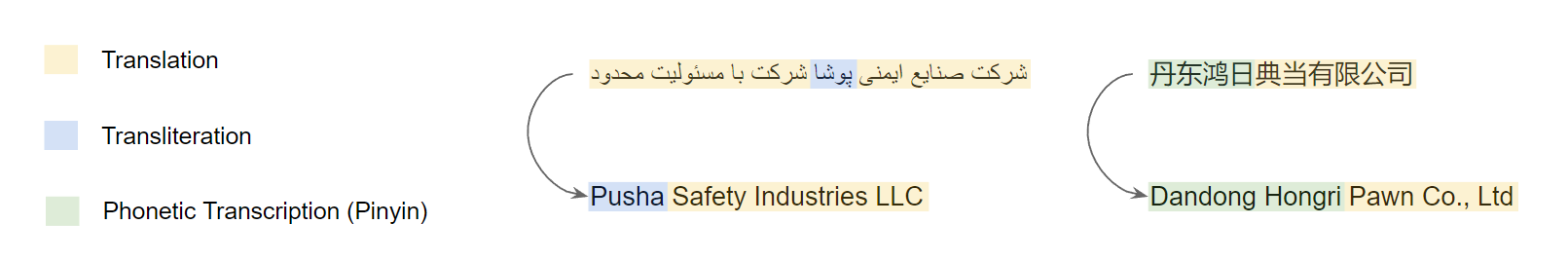

A translation expresses a word in another language based on the word’s meaning. If and how an entity does business using an English translation of its name influences how that entity may show up in public records.

Sometimes the words in a company name have one-to-one English equivalents, but sometimes there are many possible translations – or none at all. To complicate matters further, companies sometimes translate only part of their names, transliterating or transcribing other parts as in the examples below. (More on transliteration and transcription in the next section.)

While it may be obvious, it’s important to never translate people’s names, even when they appear in company names. This is an instance where Google Translate can be really unhelpful.

It’s also worth noting that in some jurisdictions, you will never want to translate company names. In Latin America, for example, companies rarely operate using English translations of their legal Spanish names. Asesoría Administrativa y Financiera de Baja California S.A. de C.V does not do business as “Administrative and Financial Advising of Baja California SA. of C.V,” so translating the company name, while straightforward, would serve no investigative purpose.

Transliteration

If translation deals with the meaning of words in different languages, transliteration is concerned with how words from one script are transcribed into the corresponding letters/characters of another script – for example, from Cyrillic to Latin letters.

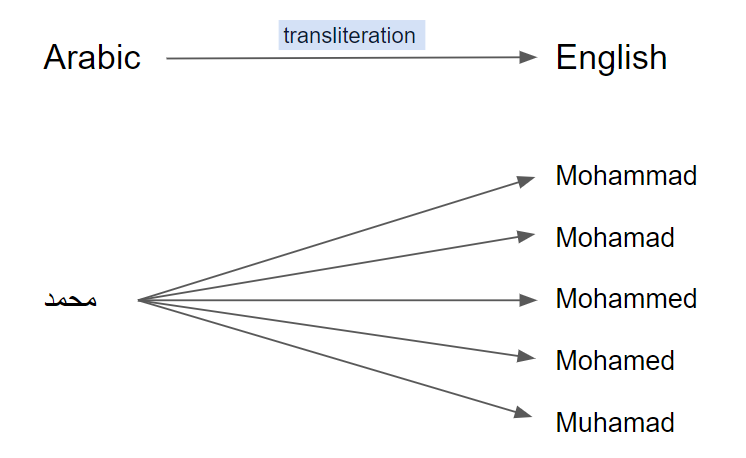

Transliteration arguably poses a bigger challenge to investigators than translation because it can lead to a far greater number of entity aliases. Failing to take all possible spellings into account can mean missing key information in an investigation.

And to be sure, transliteration can affect how the names of both companies and individuals appear on public records.

And that’s without even getting into transliterating letters and sounds that exist in other languages but not in English or the Latin alphabet, such as Arabic’s خ (kh), غ (gh), ق (q), ح (haa), and ﻉ (ayn) sounds.

Transliteration also leads to challenges during automated data analysis and list screening. A human might know the above spellings of Mohammad are equivalent, but a computer will likely have a harder time making that type of inference.

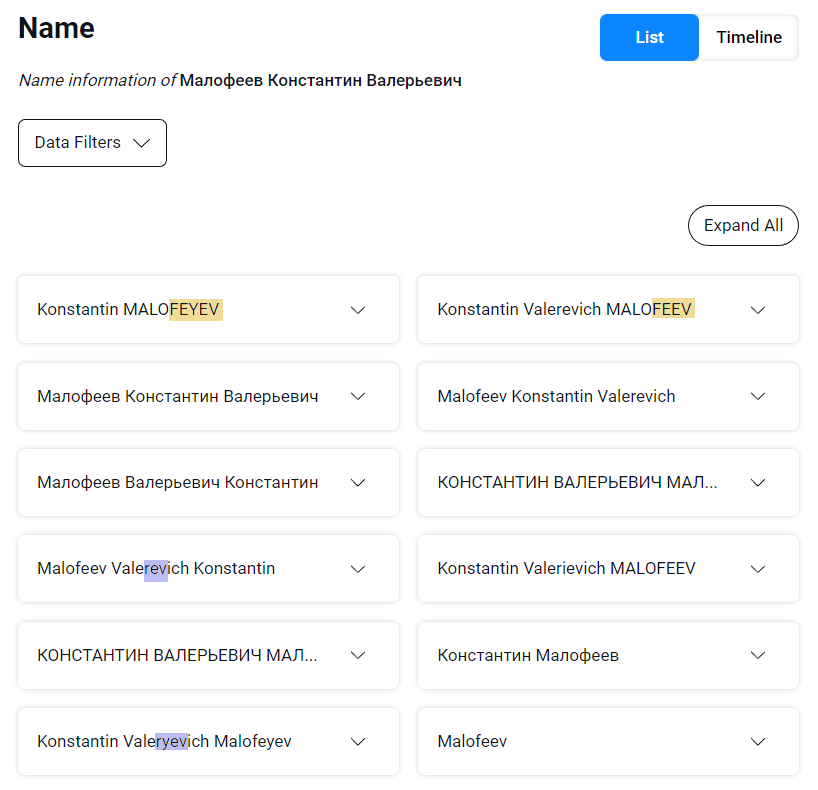

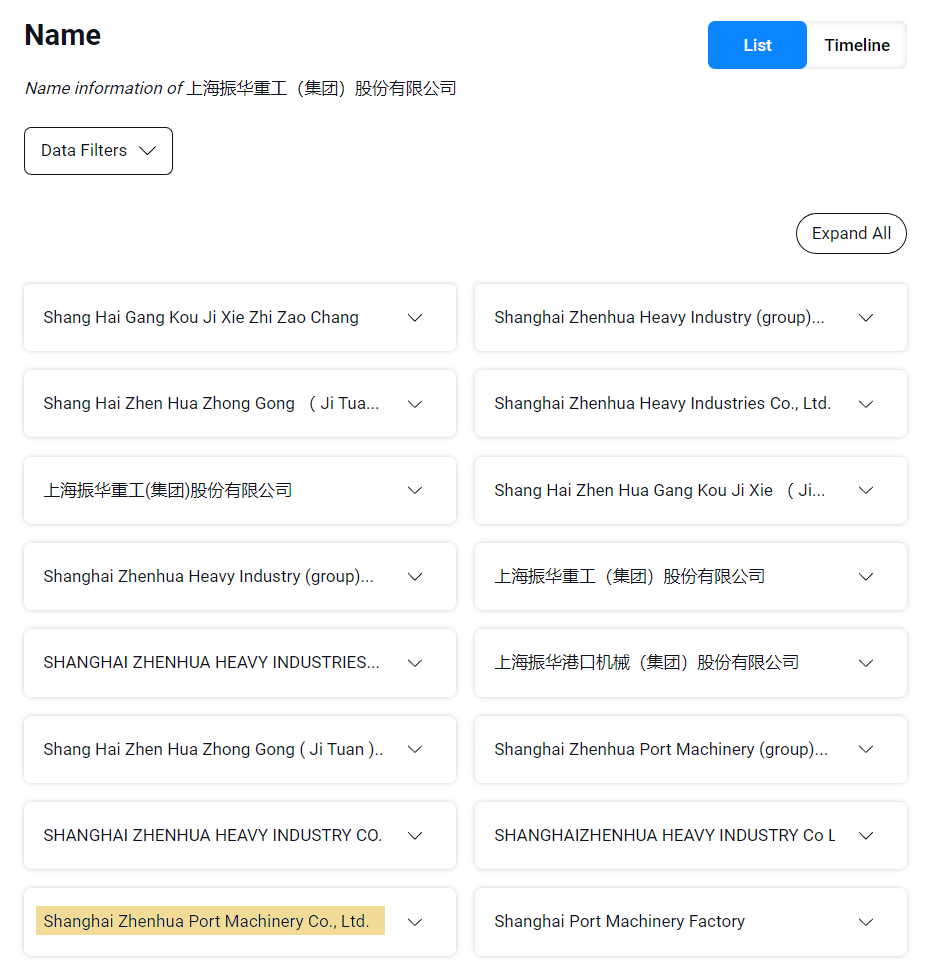

Sayari Graph helps investigators account for the many ways in which names may be transliterated in public documents by aggregating them under the Name attribute, as in the example below.

While such examples help illustrate the problem, there is unfortunately no universal standard for transliteration. Simply being aware of the fact that your target’s name may appear under a variety of spellings as a result of transliteration can go a long way in casting a wider net during an investigation.

Phonetic transcriptions

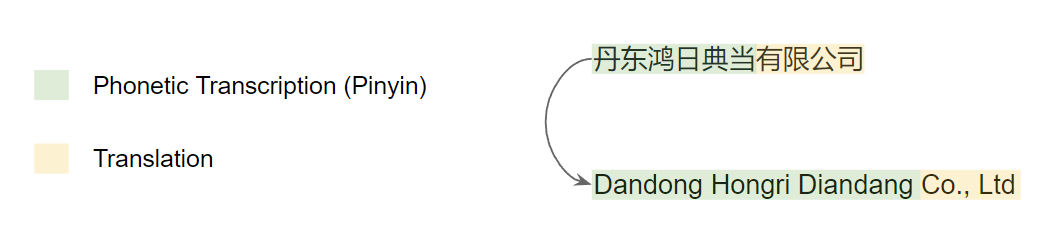

Phonetic transcriptions are similar to transliterations but apply specifically to logographic writing systems – that is, writing systems that use characters to represent words or concepts as opposed to individual letters used in phonetic writing systems like English. Chinese is the most common example.

Chinese uses a standardized system for transcribing characters into sounds that are represented by the Latin alphabet. The system is called Pinyin and allows investigators to transcribe Chinese company names into Latin script.

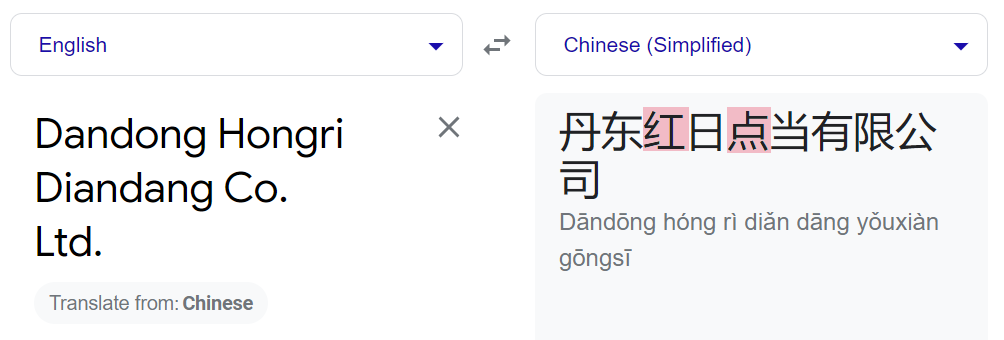

Let’s return to the earlier example of Dandong Hongri Pawn Co., Ltd. and create an English name using Pinyin instead of the partial translation.

It’s important to recognize, however, that Pinyin transcriptions are not bi-directional. You can move from the Chinese characters to the Pinyin spelling, but you can’t move from the Pinyin spelling back to the original Chinese characters (and therefore the original meaning) with any confidence. This is because multiple Chinese characters can produce the same Pinyin spelling based on their pronunciation.

Running a Pinyin name through Google Translate or another converter to return Chinese characters will likely produce the incorrect ones, leaving investigators vulnerable to costly errors.

Trade names

Trade names, also known as fictitious names or “doing business as” names, are the names by which companies are commonly known, or the names they use when advertising or doing business. These are common across the globe. It’s really important to identify trade names, as it’s easy to mistake an entity doing business under their trade name as a separate entity altogether.

Sometimes trade names will have some relationship to the legal entity name, but sometimes not. We see this play out in particularly complex ways in China, where entities can do business using:

- Their original name in Chinese characters

- An English translation of their Chinese name

- A Pinyin transcription of their Chinese name

- An English trade name that has nothing to do with their original Chinese name

- All of the above interchangeably

Consider the following example in Sayari Graph.

While this name has some similarities to the original Chinese name, it could have easily been mistaken for a separate entity altogether.

Naming conventions

Cultural nuances in how names are constructed also affect the way investigative targets – particularly natural persons – appear on public records. These differences are commonly referred to as naming conventions.

Beginning investigations by familiarizing yourself with the naming conventions practiced in the target entity’s jurisdictions will go a long way to ensuring you don’t miss any crucial details.

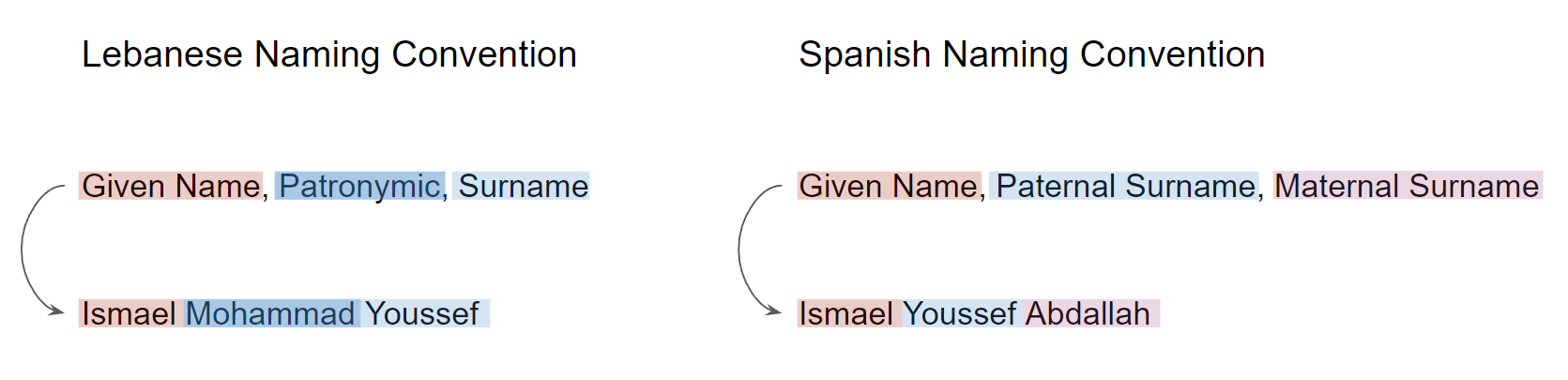

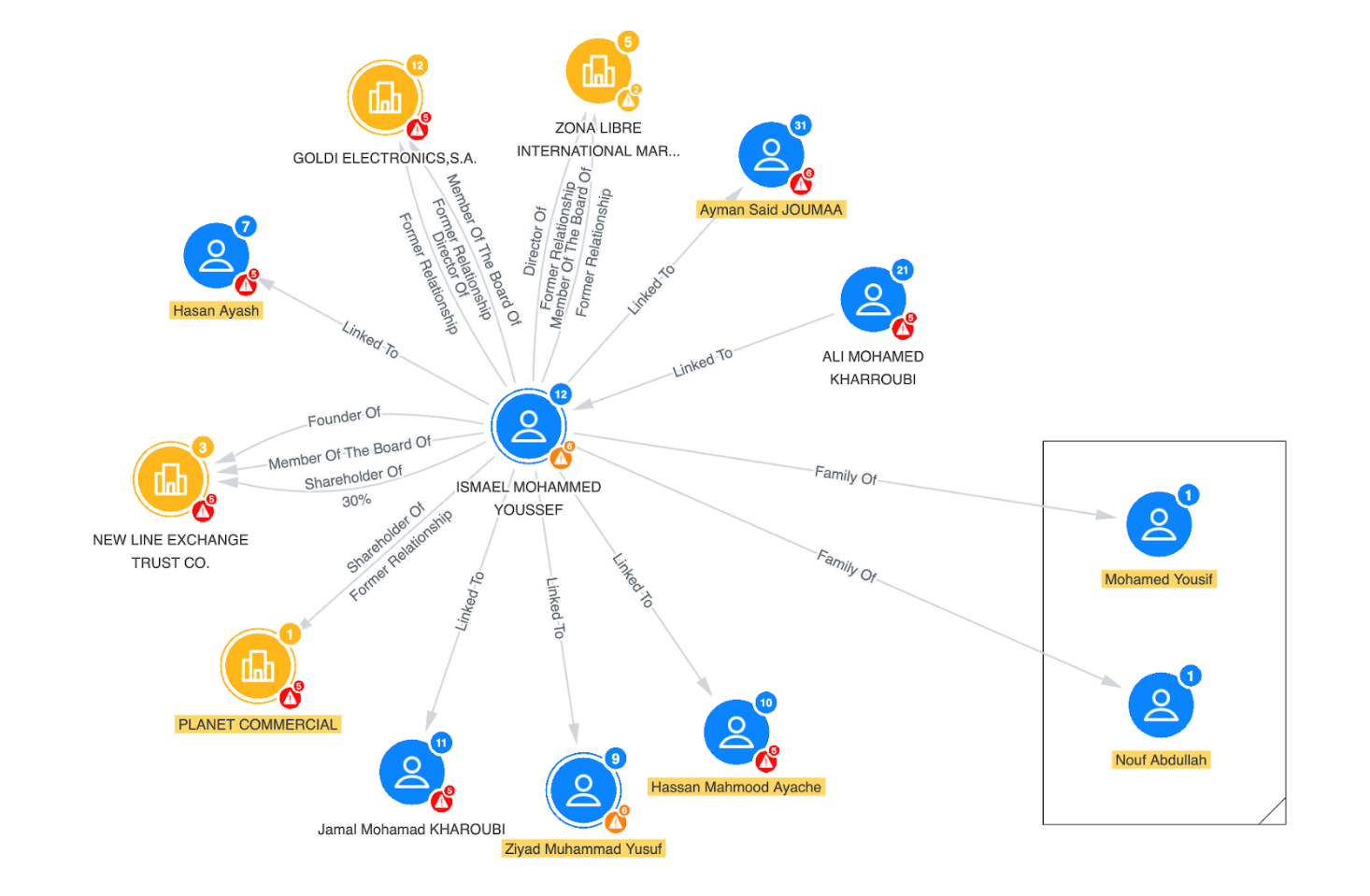

Consider, for example, the case of Ismael Mohammad Youssef, who was sanctioned by OFAC in 2011 for allegedly helping drug traffickers launder their ill-gotten gains and later removed from the SDN list in 2018.

At the time of designation, OFAC provided a possible alias, Ismael Youssef Abdallah, and stated that Youssef operated in Latin America. While it later turned out that Youssef previously controlled a number of companies in Panama, none of them listed the name Ismael Mohammad Youssef. Rather, they listed the name Ismael Youssef Abdallah because Panama abides by Spanish naming conventions.

If we were to go into the Lebanese voter rolls, which provide date of birth and family information, we’d see that Youssef’s mother’s last name is indeed Abdallah.

Had OFAC not helpfully provided both versions of Youssef’s name in the designation, it would have been easy to search Panamanian records using the Lebanese construction of his name and conclude – incorrectly – that he had no presence in Panama, missing the full picture of his holdings. This is why it’s critical to consider naming conventions in addition to spelling variations resulting from translation and transliteration.

How to “Read” Corporate Documents in Languages You Don’t Speak

After clearing all these naming hurdles and confirming you’ve identified the correct target, you still have to navigate a document written in a language you don’t understand in order to learn more. While it may seem daunting, a little research and prep can allow you to navigate public records in other languages with more confidence.

Step one: research key terms

Before you can actually begin “reading” public records from a foreign jurisdiction, you need to understand key terms that will appear in the documents. These will largely depend on what information you need in order to advance your investigation.

Key terms and concepts we typically focus on include ownership and various types of control relationships (directors, managers, legal representatives, etc.), as well as common corporate structures (e.g., limited liability companies), but this is largely dependent on what you’re trying to accomplish in your investigation.If you were looking through a Mexican trademark application, for instance, you might search for the word accionista, Spanish for “shareholder.”

It is also important to spend time researching common identifiers and figuring out which, if any, are unique to an individual and company.

The most authoritative source for this information will be corporate laws and regulations published by the governing authority or registrar, if they are provided in English. If not, looking at law firms and/or corporate service provider websites that cater to foreigners wishing to do business in the country can also be helpful to understand key terms and concepts that will appear in public records. These websites are pretty easy to find through basic internet searches using queries like “Panama company ownership.”

Step two: study document structure

Once you’ve attained a strong baseline knowledge of key terms and concepts, then you can dive into how public records in the jurisdiction are structured. You’ll want to spend time finding out which sources will provide information relevant to your investigation and get a sense of where key information appears on documents from those sources.

Highly structured public records in places like Russia and China typically include a lot of the same types of information and keywords from entity to entity.

You can apply a similar approach to unstructured documents, scanning for key words and looking for patterns in where they appear. Even without numbered boxes, something like a bulk-text incorporation filing will often be organized in a standard way, allowing you to learn the structure and more quickly identify the information you’re looking for.

Step three: extract important details

Once you’ve determined where in a given document the relevant information is, you can easily extract it and move on to the next document, gathering speed as you become increasingly familiar with the key terms and record types.

Note that you may need to translate individual and company names several times over before concluding your investigation. If you want to translate blocks of text for added context, Google Translate and other machine translation tools can be useful.

Investigative Examples

The examples in this section apply the above techniques in real-world investigative scenarios. The first uses a short Russian asset tracing investigation to illustrate how to anticipate changes in an individual’s name as a result of transliterations and naming conventions. The second simulates a very common challenge facing anyone doing investigations in China: namely, how to go about identifying ownership and control of a company when you only have the company’s English trade name.

Naming conventions and transliterations in practice

Let’s say we’re interested in identifying assets owned or controlled by Ziyavudin Gadzhiyevich Magomedov, a Russian oligarch and the founder of a large Russian investment company called Summa Group who in 2018 was arrested and charged by Russian authorities for forming part of a criminal organization and embezzling upwards of $35 million.

In this scenario, we’ll imagine we only have Magomedov’s full name and a month and year of birth: September 1968. To use this information effectively, however, we must first put his name in the appropriate cultural context:

1. Identify the target jurisdiction

We’ll say for the sake of this example that our goal is to identify Magomedov’s assets in Western Europe.

2. Identify the jurisdiction’s naming conventions

Patronymics are not part of Western European naming conventions, so when we search for Magomedov – be it in a commercial risk intelligence platform like Sayari Graph, Google, or a Western European corporate registry – we will leave out “Gadzhiyevich.”

3. Anticipate and control for alternative spellings

Some experimental searching reveals that “Ziyavudin” can be transliterated from Cyrillic to Latin characters in a variety of ways. If we’re searching Sayari Graph or Google, we can broaden our search and catch these alternative spellings by using the ~1 Boolean operator, which allows for per-character variation. If we’re searching a database that doesn’t support Boolean operators, we can instead search the name variations we discover through our “fuzzy” Google search.

4. Corroborate using other entity attributes

Once we’ve narrowed our target results to a couple of possible candidates, we can use Magomedov’s birth month and year to confidently pick the correct result from the list.

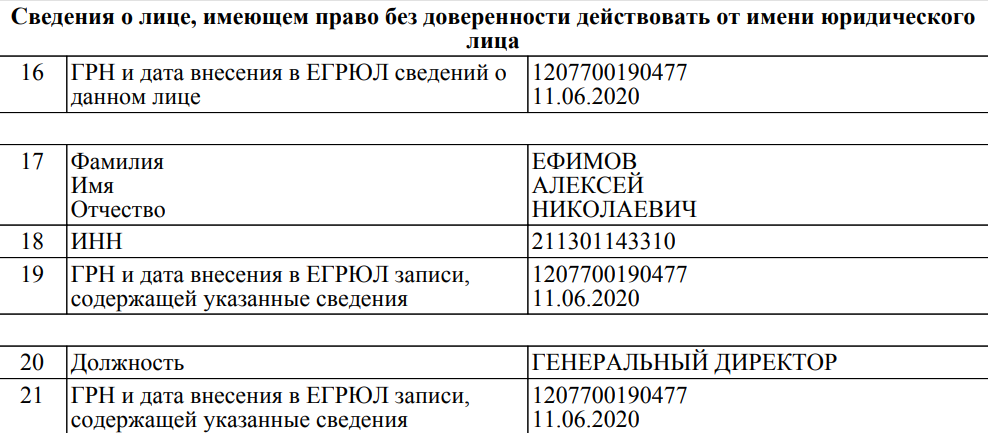

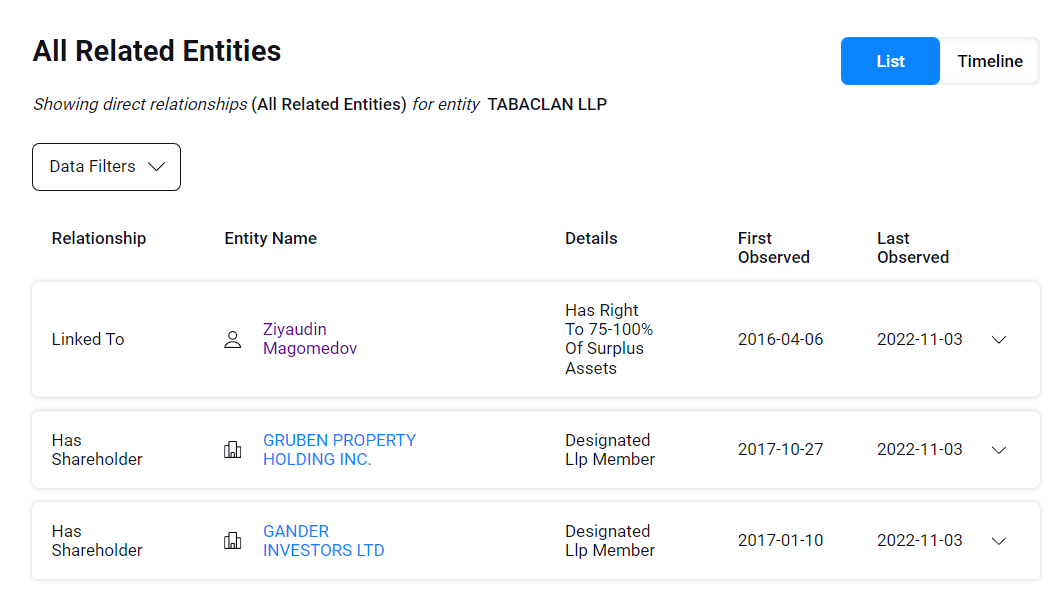

Applying these steps in Sayari Graph, we see that Magomedov is listed as a Person of Significant Control for a now-defunct UK limited liability partnership called Tabaclan LLP. However, instead of showing up as “Ziyavudin,” his name is written “Ziyaudin.”

Interestingly, we see that the direct shareholders – or LLP members – are two British Virgin Islands-registered shell companies: Gruben Property Holding Inc. and Gander Investors Ltd.

Identifying Magomedov as the ultimate beneficial owner alongside two shell companies that served as the direct shareholders suggests that Magomedov may have owned Tabaclan via these shell companies at the time of closure. (This is, incidentally, an example of how to unmask companies registered in notorious secrecy jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, which you can get more tips and tricks on in our masterclass and report on the subject.)

Had we not accounted for naming conventions and name variations as a result of transliteration, we would have missed all of these details surrounding Magomedov’s assets.

Deriving Chinese names from their English versions

Let’s say for the sake of this next example that you need to conduct an investigation into Chinese company Tekon Biotech (Shanghai) Ltd., and all you have is its name in English. You want to learn everything you can about its commercial network, especially who owns it.

1. Search using the English version of the name – just in case.

Certain Chinese government databases will disclose an official English trade name for some companies if they have one, so it’s always worth trying the English names, even if you know a hit is unlikely.

In this case, searching Chinese corporate filings through Sayari Graph yields no results for “Tekon Biotech (Shanghai) Ltd.”

2. Search using a direct translation of the English name.

Using machine translation to move from an English name to the original Chinese name is often unsuccessful but still worth trying in the unlikely event that the English name was a direct translation.

In our case (and in many cases), this doesn’t work, indicating that we could be dealing with the company’s official English trade name rather than an English translation of the original name in Chinese.

3. Find a self-disclosed Chinese version of the name.

Since we didn’t have any luck translating our way from English to Chinese, we instead need to find the company’s original name in Chinese characters through a bit of open source research. Identifying the legal name in Chinese increases our chances of finding the company in Chinese public records and, consequently, the company’s owners and other related parties.

One effective way to identify company names in Chinese is to first look for the company’s website. Many Chinese companies will provide English and Chinese versions of their websites – often within the same website domain. Finding the company name on the English site, then toggling over to the Chinese version and retracing your steps to that spot, is an effective way to get the original name.

Querying “tekon biotech (shanghai) ltd.” in Google returns the company website as the first result. Its About Us page features the company name prominently. All we have to do to find the Chinese name is remember how to navigate to the About Us page, toggle to the Chinese site, and repeat those steps.

Keep in mind, however, that there may be major navigational differences between the English and Chinese versions of a site. Searching for the Chinese characters for “limited liability company” (有限公司) can help you locate the name despite these differences. These four characters rarely show up alone in bulk text on a company website, so you can usually assume that at least some of the characters preceding it are part of the company’s name.

In some cases, the Chinese version of the site might be on a different domain – or not exist at all. In those cases, you can try to look up the original domain registrant using open source domain aggregators like Who.is. Conducting this check, we see that the same Chinese name we previously found on Tekon’s website is listed as the domain registrant.

If you cannot find the company website at all, the next most reliable place to look for this self-disclosed name is news media, particularly if you have one or two other identifying attributes to go on, such as an English address or the name of an associated person.

4. Query the Chinese name against Chinese public records.

Now that we’ve identified the company’s original Chinese name, we can then run this name against Chinese public records in Sayari Graph to identify who owns or controls it. We should highlight that the English translation of the company’s Chinese name is Shanghai Dianao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. This name bears no resemblance to our original input – Tekon Biotech (Shanghai) Ltd. – suggesting that Tekon Biotech is likely the company’s English trade name.

It turns out that Shanghai Dianao Biotechnology (aka Tekon Biotech) is ultimately owned by an individual named Zhang Zhengfeng, via an intermediary company called Dianao Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd, according to Chinese public records.

Conclusion

Conducting investigations in languages you don’t understand can be tricky, but there are ways to become proficient at it. Anticipating how targets’ names may change in different languages and jurisdictions, and becoming skilled at “reading” foreign corporate filings, will set you up for success in any cross-border investigation.

These are practical techniques that our Sayari analyst team has developed over years of experience in public data investigations. They practice them almost daily in support of our customers and partners – and in our own investigative projects.

For more practical investigative tips and tricks with illustrative examples, browse our library of recorded masterclasses, or register for a future masterclass in our Resource Center. Registration links are posted several weeks in advance, and the next one will center on methods of entity disambiguation.

For access to over 2.8 billion records from 250+ jurisdictions worldwide, request a personalized demo of Sayari Graph today.

About Sayari

Sayari empowers government and industry to protect finance, trade and security systems by illuminating the global commercial networks through connected public data and documents. Providing commercial intelligence data from over 250 jurisdictions worldwide, Sayari delivers the entity network visualizations and intuitive risk identifications that decision makers need to stay proactively informed and power safer global commerce.

Since its founding in 2015, Sayari has earned the trust of top financial institutions, Fortune 100 corporations and government agencies, securing a $40M Series C in 2021. Sayari is headquartered in Washington, D.C., and its solutions are used by more than 3,000 frontline analysts in 35 countries.