The Middle East can be a lucrative business environment due to the continued liberalization of foreign investment laws and its relatively large and young working-age population. Unfortunately, the region suffers from a dangerous combination of public corruption and weak anti-corruption enforcement mechanisms, which results in instances of major corruption cases involving high-level government officials and other politically exposed persons (PEPs).

In this investigation, we used public records to trace the assets of a Lebanese PEP, some of which may have been obtained through or used for corrupt acts. Whether part of pre-investment due diligence or general asset tracing, investigators need to be aware of the risks associated with operating in the Middle East and how to use public records to trace assets in the region.

Anti-Government protests focus on public corruption

Recurring anti-government protests across the Middle East since 2011 have made corruption a major target, and with good reason. In Iraq, some experts believe that corruption is the main threat to state stability following the defeat of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Some estimates put the amount of state revenue lost from graft between 2003-2018 at $320 billion.

One of the most lucrative forms of corruption in Iraq is contracting. Since 2003, public officials have approved egregiously overpriced public contracts to earn a profit for themselves and their personal or political connections. In one such instance, the Iraqi government purchased warplanes for $13 million each, when they were valued at only $975,000 USD each.

More recently, powerful militias have extorted business owners into either providing them with part of their business’ profits or forcing the owners to hand over the entire operation, as was the case with a services contract at Baghdad International Airport.

In Lebanon, public services failures like the trash crisis that started in 2015 and led to images of trash lining the streets of Beirut, embody the country’s endemic corruption. As a temporary measure, the government awarded two contracts for two new landfills. A businessman that is said to be close to the Lebanese president’s family won one of the contracts worth $142 million, according to The New York Times. The other, worth $288 million, went to Jihad Al-Arab, someone closely linked to the former prime minister of Lebanon, Saad Al-Hariri.

A recent tragedy also has its roots in Lebanon’s public corruption problem. A warehouse fire in August at a Beirut port ignited approximately 3 tons of ammonium nitrate, which caused a blast that killed at least 212 people, demolished significant parts of the city, and left thousands homeless. Lebanese authorities confiscated the ammonium nitrate from an abandoned ship nearly six years prior and left it in a warehouse lacking proper safety measures. Analysts blame widespread corruption and sectarian power sharing within Lebanon’s government for allowing the conditions to exist for such a horrific and avoidable incident.

OFAC sanctions high-ranking Lebanese politician

The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) uses, among other enforcement mechanisms, the Global Magnitsky Act (GLOMAG) to sanction corrupt actors and human rights offenders, including those in the Middle East. In its latest action targeting allegedly corrupt actors in the Middle East, OFAC sanctioned Gibran Bassil under GLOMAG on 6 Nov., 2020 for “his role in corruption in Lebanon.”

Bassil is a high-ranking Lebanese politician who heads the Free Patriotic Movement, a Hezbollah-aligned, Christian political party. Using public records in Lebanon, including corporate and real estate data, investigators can trace Bassil’s assets that could be linked to his alleged corruption.

Bassil’s commercial ties to the President of Lebanon

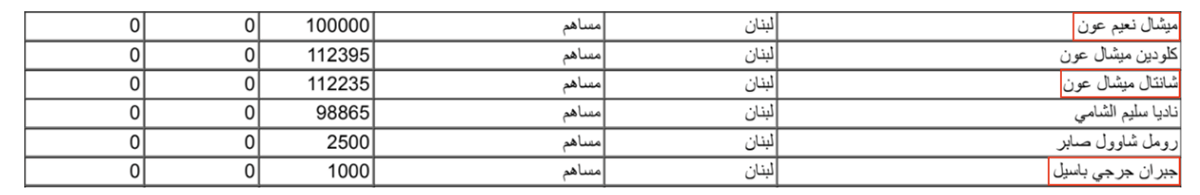

Records from Lebanon’s corporate register list Bassil as a founder and/or shareholder of at least five companies in Lebanon linked to media, real estate, and construction. Michel Naim Aoun, the President of Lebanon, holds shares in one of those companies, OTV Holding SAL. Aoun’s daughter, Chantel, is married to Bassil and is also listed as a shareholder.

Fig.1: A snapshot from Lebanon’s corporate register that highlights shareholders (top to bottom): Michel Aoun, Aoun’s daughter, Chantel, and her husband Gibran Bassil.

One of Bassil’s companies, Aamar Engineering and Construction, lists “contracting” within its stated business purpose. Contracting in Lebanon, similar to Iraq, is a high-risk industry. The Basil Fuleihan Finance Institute, the knowledge arm of the Lebanese Ministry of Finance, describes Lebanon’s public contracting process as “outdated and fragmented…resulting in inefficiencies and high risks of corruption.”

Considering Bassil’s relationship to Aoun, Aoun’s alleged history of awarding those close to him, and Lebanon’s public contracting environment, it is possible that Bassil is at risk of or already has grown his assets through this connection, whether through contracting by Aamar or his other companies.

Bassil’s property listed in Lebanon’s property records

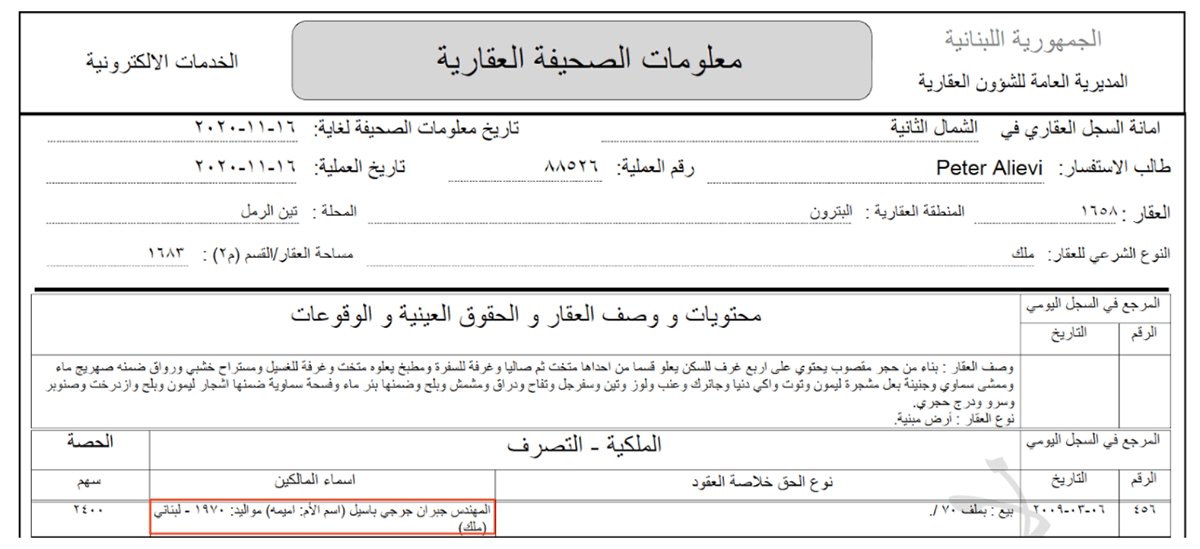

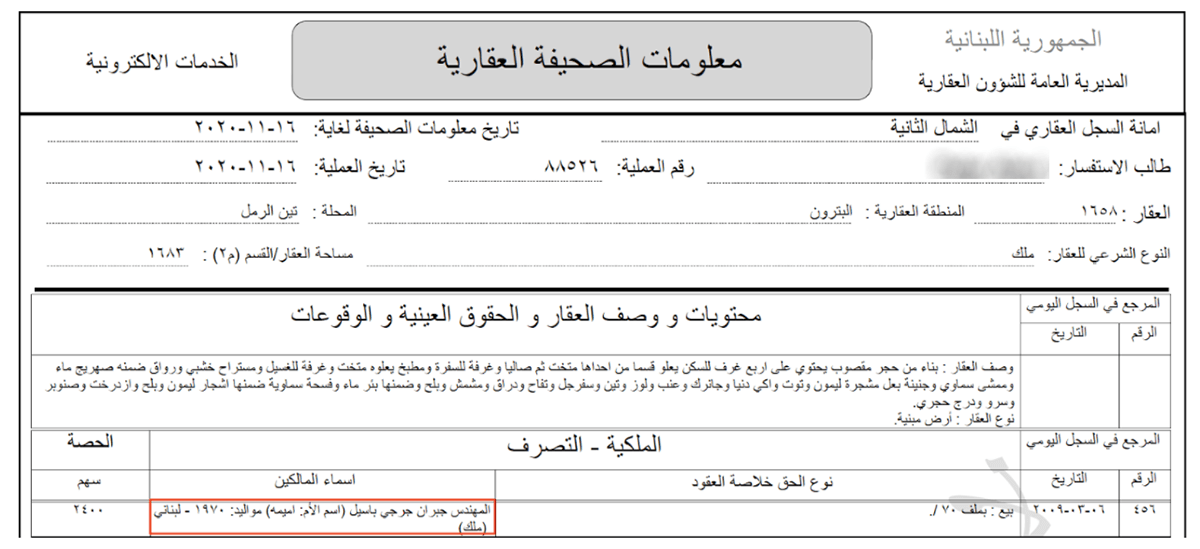

Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance oversees the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (LRC). The LRC maintains an online database of land records from the eight governorates that comprise Lebanon.

Records from the LRC list property owned by Bassil at an address associated with Aamar Engineering and Construction. The listing includes relevant personally identifiable information (PII) including Bassil’s birth year and his mother’s name — both of which match Bassil’s PII in the Lebanese voter records.

Local media suggests that Bassil used his connections as Michel Aoun’s son-in-law to build his real estate empire, which includes 38 properties in Bassil’s hometown of Batroun — the same town listed on the document above. Unfortunately, we cannot find all of Bassil’s properties in the LRC database without exact addresses, something that is not always provided in Lebanon’s corporate register or in other open sources.